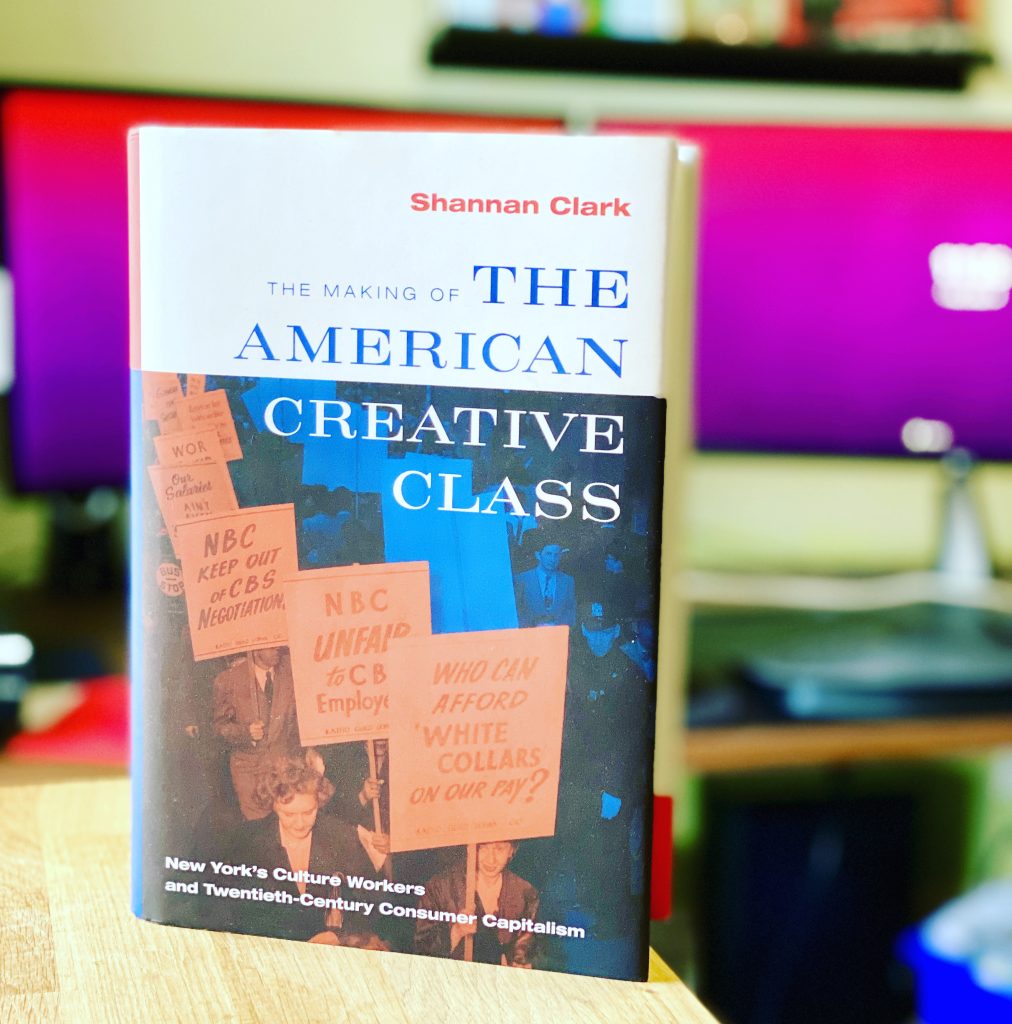

A scholarly history of workers in media, publishing, design, advertising, and related professions in New York from the 1930s to the 1970s. Across the decades in which capitalism took on a mass consumerist shape, it traces changes in these industries that were so central in that process. And it examines the ways in which workers in these industries fought for better wages and conditions through unions, intervened politically in sometimes radical ways, and in the early period advanced visions for a quite different sort of mass culture via a range of alternative institutions. I read this, after hearing an interview with the author, because I have vague notions of doing writing in the future that thinks through how these kinds of work – which encompass the kind of work that I do, in my own way – and the people who do them can have an impact on the world. This book was a stimulating input for that reflection because not only does it show where today’s mainstream institutions in those industries came from, but it also shows a far-away-seeming time and place in which lots of culture and media workers were part of thriving, multifaceted movements for social transformation. This was the era of the Popular Front in the late 1930s and the 1940s, when collaboration among Communists, non-Communist socialists, and liberals produced a thriving mix of movement institutions of all sorts and a social democratic political and popular culture with a mass base in urban areas in the US. This history evokes a rich sense of a fleeting moment that carried the seeds of what could have been quite a different world – and, like, I don’t even mean a world in which some hypothetical revolution swept away capitalism in the United States or anything that dramatic, but just one in which vibrant institutions of the left survived to the next generation. Of particular interest to me, the book talks about some experiments in the 1940s with left mass media organizations. It’s also fascinating to see that certain things that we are taught to see as developments of a later era, like the fight against racist and sexist discrimination in the workplace, was something that some Popular Front white collar unions were taking up in important ways in the ’40s. But, sadly, while there was this moment where it seemed like things could be different, of course another important part of this history is the mobilization of state power in the US in the early years of the Cold War to destroy the left – and it was a useful reminder, very relevant to our current era, that the goal of the right in the US has never just been defeating its opponents, but destroying them. It was hard to read some of the stuff about the late ’40s and the ’50s, frankly. And the material covering the ’60s and ’70s was less exhaustive, with a focus on industry changes and union struggles and also a little bit about New Left interventions, particularly in print and broadcast media industries. Which was also interesting in its own way. (I wouldn’t mind knowing more about analogous histories for Canada over the same period. Toronto was a pretty provincial place back then, and I know that the Popular Front had a reach and momentum in the US that it never attained here, so I expect things played out rather differently.) Overall, this is a long, detailed, very conventionally written academic history, so it is certainly for a niche sort of reader. But if the history of culture and knowledge workers as political actors is something that interests you, it’s certainly worth the effort.

Originally posted by Scott on Goodreads.