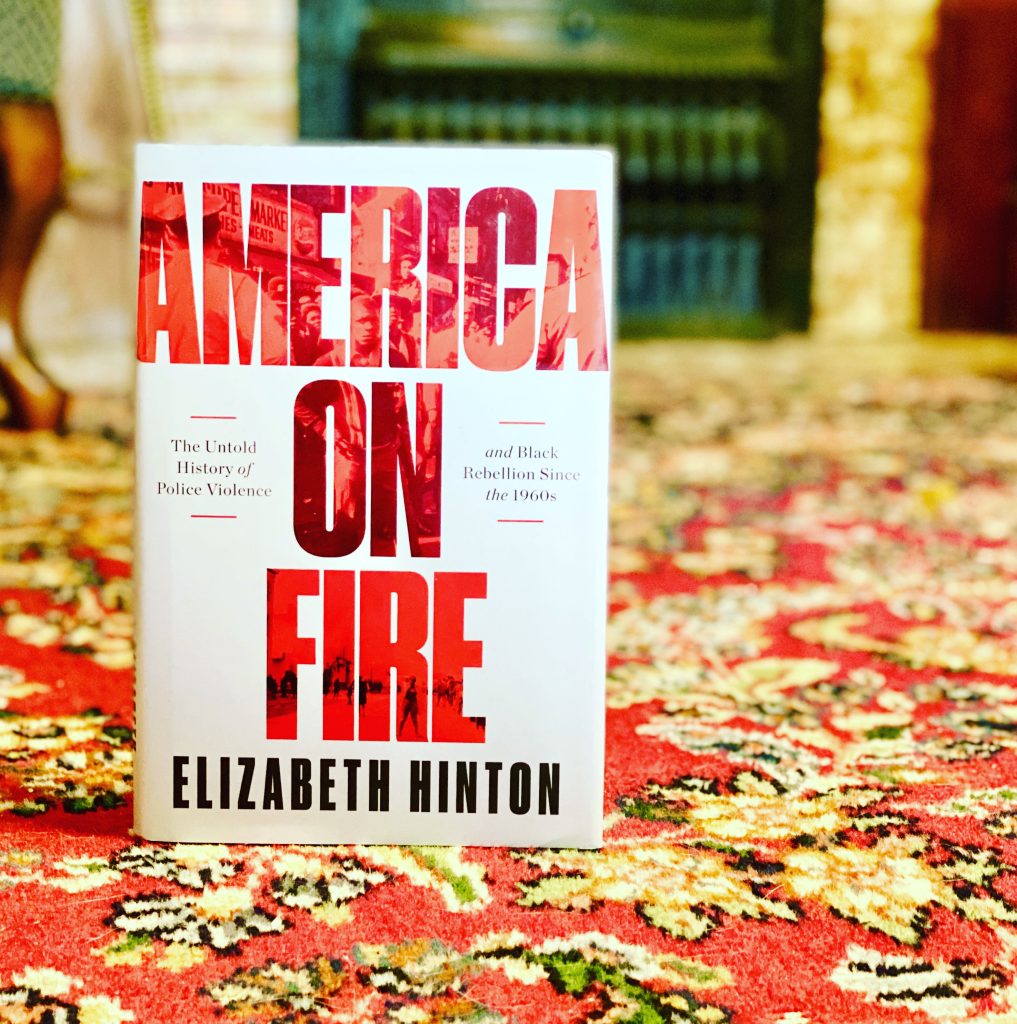

By a professor of history and African American studies at Yale, this book examines the history of urban rebellions – often called ‘riots’ by official sources – in US cities from the mid-1960s to the present day. Though today we most often remember only the highly publicized uprisings in the largest cities in the mid-to-late 1960s, in fact there were a huge number of rebellions in small and mid-sized cities across the US lasting well into the 1970s. These rebellions in smaller centres are much less well documented overall, and Hinton focuses on them for the earlier part of the period she covers. The basic finding of the book is that across very different cities and very different political moments, police violence is almost always the proximal trigger for urban rebellions, in the context of longstanding generalized oppression and consistent refusal to meet community demands presented in other ways. In the wake of the turn to law-and-order policing later in the 1960s as the primary state response to ongoing political mobilization in Black communities, urban rebellions were usually triggered police violence in a relatively ordinary, everyday form. By the 1980s, the pattern had changed somewhat. The increasingly overwhelming militarized power of US police forces shifted the calculus of rebellion for communities but nonetheless continued to make it inevitable, so uprisings since the Miami riots of 1980 have tended to happen much more rarely and only in response to the most egregious instances of police misconduct, but have tended to be larger and more intense.

Along with the important insight into the central role of police violence in triggering both nonviolent and violent community responses, this book is also a fascinating look at how racial justice and policing-related struggles took place in contexts that most histories of civil rights and Black Power neglect – i.e. smaller cities, particularly smaller cities post-1968, often in the absence or only fleeting presence of big-name leaders. And it’s hard for me to be as concrete about why I say this as I would like, but there is something about the history described in this book that helps make aspects of contemporary political life in the US make more sense at an embodied, felt level, whether that is some of the dynamics surrounding the racial justice uprisings of 2020, or some of the specifics of the anti-Black stereotypes that right-wing and liberal pro-police commentators deploy, or even why “defund the police” is such an important demand – not that I had any doubts about that, but seeing how commissions and consultations and reform efforts have been trotted out periodically for 50 or 60 years at all levels of government and still all of this continues to happen makes it clear that removing resources from the institutions that do harm and creating new ways of meeting community needs are the only way forward that might fundamentally change things.

Important history and a good read.