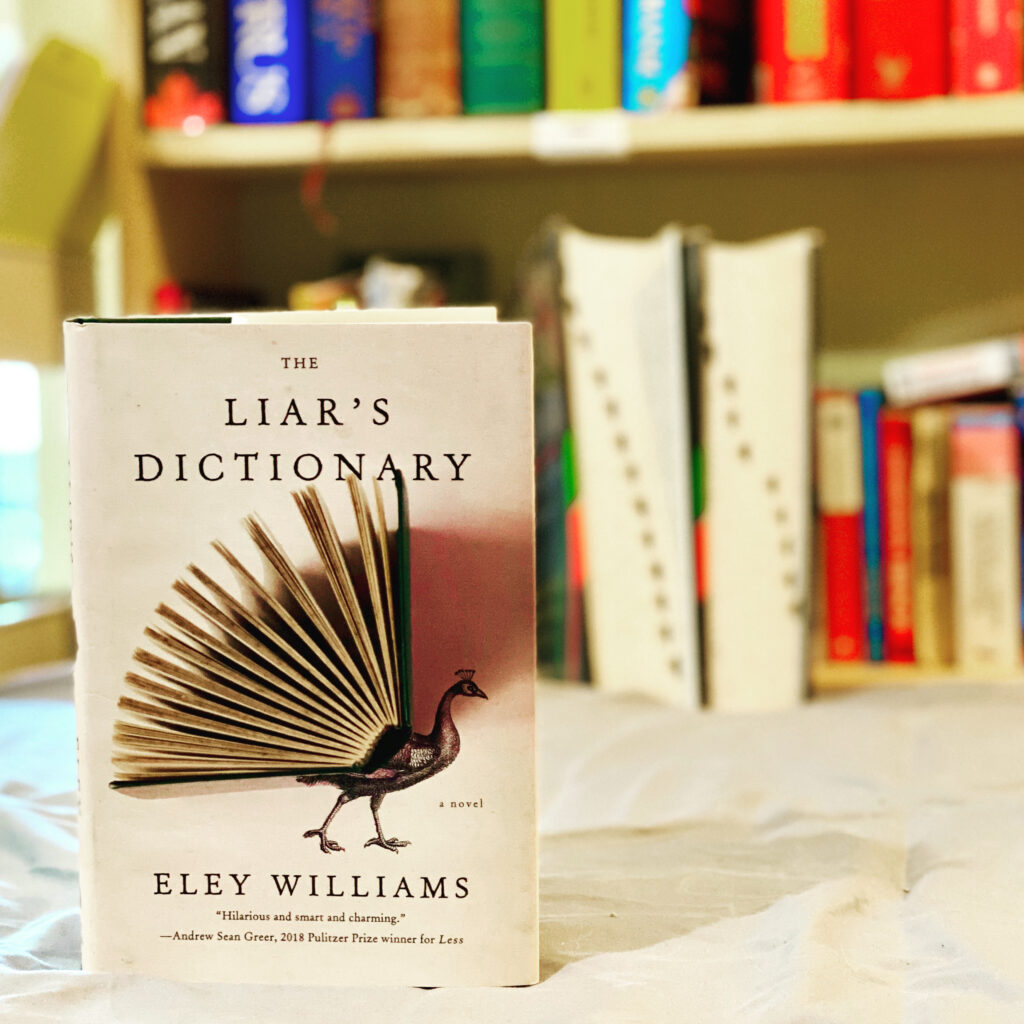

Literary fiction. Two interspersed narratives set in London, England, one in the Victorian era and one in the present day, each following an employee of the same encyclopedic dictionary. In the older time period, it is a bustling concern, with dozens of lexicographers filling a massive building, working slowly towards the hoped-for publication. That blessed event (not shown) took place in the 1930s, but we are told that it went down in history as the only one of the great English-language dictionary projects published without actually being finished, which has made it something of a literary laughingstock through the decades. In the present day, the only employees of the dictionary are the septuagenarian great-grandson of the original owner/chief editor, who spends his days playing chess on an ancient computer and occasionally puttering around at digitizing his inheritance, and a young woman working as an intern. The massive building is the same, though the lower floors are sometimes rented out for events and most of the upper floors are empty. The narratives follow a lexicographer back in the day, and the intern today. Both are unfortunate, hapless, timid souls – observers of life, but reluctant livers of it. The former actively dislikes working at a dictionary as well as most of his colleagues, and the latter seems largely indifferent to the industry of her employer and just wishes she wasn’t the one who had to field calls from a regular, rage-filled voice belonging to someone not pleased that the definition of “marriage” was updated to fit the times. The connection between the narratives, beyond their temporally distant but institutionally and physically shared settings, is that the lexicographer ultimately decides to insert a series of made-up definitions into the dictionary; the intern is tasked by the embarrassed latter-day owner/editor with tracking them down so that they might be removed during the digitization process.

It is a quiet book, not short but in a particular sense of the word quite small, and it is clever. The author clearly loves language and uses it well. There are perhaps a few spots where it goes overboard in the way that a work of literary fiction centred on a dictionary is almost inevitably going to do. Both storylines were deliberately peculiar, but while I think I liked the intern better and would much rather hang out with her, the lexicographer’s story was a bit richer and more interesting. Overall, not spectacular, but I enjoyed it. Extra points for, on the first page, describing a typeface by comparing it to Jeremy Brett, my favourite Sherlock Holmes.

Originally posted by Scott on Goodreads.